Quick Facts

Died At Age: 84

Family:

father: Festus Flipper

mother: Isabelle Flipper

siblings: Carl Flipper, Emory Flipper, Festus Flipper;Jr., Joseph S. Flipper

Born Country: United States

African American Slaves Soldiers

Died on: April 26, 1940

U.S. State: Georgia

More Facts

education: United States Military Academy, Clark Atlanta University

Early Life & Education

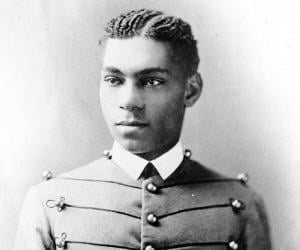

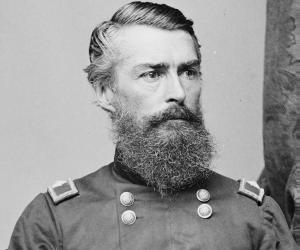

Flipper was born on March 21, 1856, in Thomasville, Georgia. He was the eldest of six sons born to Isabelle Flipper and Festus Flipper. His father was a shoemaker, and a carriage-trimmer. His parents were owned by an affluent slave owner named Ephraim G. Ponder. Flipper attended the ‘American Missionary Association Schools’ in Georgia.

As a freshman at ‘Atlanta University,’ Representative James C. Freeman appointed Flipper to the military academy at West Point, where white students excluded him from all activities. Despite challenging times, in 1877, he became the first ”black” to graduate and the regular army’s first and only ”black” commissioned officer.

Flipper was the first non-white officer to lead the ”buffalo soldiers” of the ‘10th Cavalry Regiment.’

Military Service

From 1878 to 1880, Flipper served at various stations in the southwest, including Fort Sill, Fort Elliott, Fort Concho, Fort Quitman, and finally Fort Davis. Apart from scouting, he served as an engineer surveyor and a commissary officer.

Flipper supervised the construction of roads and telegraph lines from Fort Sill to Gainesville, Texas, appropriate both for military and civilian purposes. It was a project that white officers had previously failed to complete. He even performed duties such as draining a malaria-infested swamp.

In October 1877, Flipper was recruited to the ‘A’ Troop at Fort Concho in West Texas.

Flipper was saddened to depart from Fort Sill and moved to Fort Elliott on February 28, 1879, where he met Miss Mollie Dwyer. Mollie was the sister of the “de facto” commander Captain Nicholas Merritt Nolan’s second wife, Anne Eleanor Dwyer.

Mollie and Flipper became friends and often spent time together. Nolan named Flipper his assistant and eventually received high marks from him. However, Mollie and Flipper’s friendship, which was considered a prohibited association of a ”black” and a ”white,” caused Nolan to go against him. Flipper and Mollie exchanged letters that triggered rumors and hinted at indecencies against them.

Flipper and Nolan, however, met again, but for the last time, during the Victorio Campaign in May 1880. Even though he had the support of some officers, such as Nolan, and many white civilians, it was a time when Flipper’s military career was troubled by racism, segregation, and plots against him.

In 1880, Flipper became the post quartermaster and commissary officer at Fort Davis in West Texas. He played a role in the Apache Wars.

Court Martial

Flipper happened to discover that a shortage in his post commissary officer’s fund had been deliberately concealed. He realized that the discrepancy could be used against him and hence decided to hide it. When later discovered, Flipper lied about covering the differences.

Even though he was not charged with misappropriation of funds, a general court-martial declared Flipper guilty of conduct unbecoming an officer and he was hence discharged.

Flipper was court-martialed on September 17, 1881, at Fort Davis. He was dismissed dishonorably on June 30 the following year.

Later, it was argued that his close association with Mollie was the real motive behind his dismissal, despite him being innocent. Two white officers who were the real culprits were not dishonorably dismissed, which proved a racial motivation as well. President Chester A. Authur turned down a request to consider a change in Flipper’s court-martial verdict.

Flipper’s subsequent years were spent in challenging the judgment and attempting to get a clean chit.

Civilian Life

As a civilian, Flipper served as a surveyor, a civil and military engineer, an author, a translator, a newspaper editor, and a historian in El Paso, Texas, until 1919. His fluency in Spanish got him a job as a folklorist in Arizona and New Mexico in the US and in Mexico. He saved several acres of disputed land in the Southwest territory.

He was also employed at the ‘Justice Department’ and worked as a special aide to the ‘Alaskan Engineering Commission.’

From 1883 to 1919, Flipper enjoyed the honor of being the nation’s first African–American civil and mining engineer. He moved to Washington, D.C, in 1921, where he assisted former U.S. Senator of New Mexico, Albert Fall. In 1923, a Texas-based oilman named William F. Buckley Sr. appointed Flipper as an engineer in the petroleum industry in Venezuela.

Writing Works

While stationed at Fort Sill, Flipper wrote an autobiography titled ‘The Colored Cadet at West Point’ in 1878. It is considered the best description of the condition of ”black officers” at West Point at that time.

He completed his second autobiography in 1916. An edited version, titled ‘Negro-Frontiersman, the Western Memoirs of Henry O. Flipper,’ by Theodore D. Harris, was later published in 1963. It chronicled his life as a civilian in Texas and Arizona.

While serving at the ‘Department of Justice’ in 1895, Flipper wrote ‘Spanish and Mexican Land Laws: New Spain and Mexico.’

Death

Flipper lived a solitary life until his death on April 26, 1940, in Georgia.

Legacy

Despite Flipper’s numerous accomplishments, he is still remembered as a victim of racism in the military.

In 1976, President Jimmy Carter granted Flipper an honorable discharge from the United States military. In 1994, his dismissal and court-martial were filed to be reviewed, and on October 21, 1997, a private law firm, ‘Arnold & Porter,’ represented Flipper to clear the charges on him and restore his rank. He finally received a full presidential release on February 19, 1999, from President Bill Clinton.

The ‘Henry O. Flipper Award’ is presented annually to graduating cadets at the West Point academy.

The letter that Flipper had written to representative John A. T. Hull on October 23, 1898, proving the injustice meted out to him and pleading an honorable discharge, is currently owned by the ‘National Archives and Records Administration.’

The drainage system that Flipper designed at Fort Sill to prevent a malaria epidemic is known as ‘Flipper’s Ditch.’ Commemorated by a bronze marker, the fort is listed as a “National Historic Landmark.”

See more: